Resource links

Is The Morning-After Pill Accessible in Singapore? | Singapore, Unfiltered

Emergency Contraception 101 at the International Conference of Family Planning

Emergency Contraception Pills – Medical and Service Delivery Guidance

Internal Planned Parenthood Federation (IPFF): IMAP Statement on emergency contraception

World Health Organization (WHO): Emergency Contraception factsheet

The Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare of the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (FSRH): FSRH Clinical Guideline: Emergency Contraception

In 2022, WHO included the recommendation of “making emergency contraception pill available without prescription”, in its guidelines on “Selfcare interventions for health and well-being”.

The recommendation was based on the systematic review conducted by WHO in 2021: Atkins K, Kennedy CE, Yeh PT, Narasimhan M. Over-the-counter provision of emergency contraception pills: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;12(3):e054122. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054122.”

Publications

This page contains a selection of resources developed by APCEC as well as partner organizations that are relevant to EC access and availability in the Asia-Pacific region.

Resources and publications:

- Emergency contraception guidelines

- Issue papers for programs and advocates

- Emergency contraception laws and policies

- Additional family planning and reproductive health resources

Provision of emergency contraception: a consensus statement

Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health COVID-19 Coalition

Recommendations for primary care

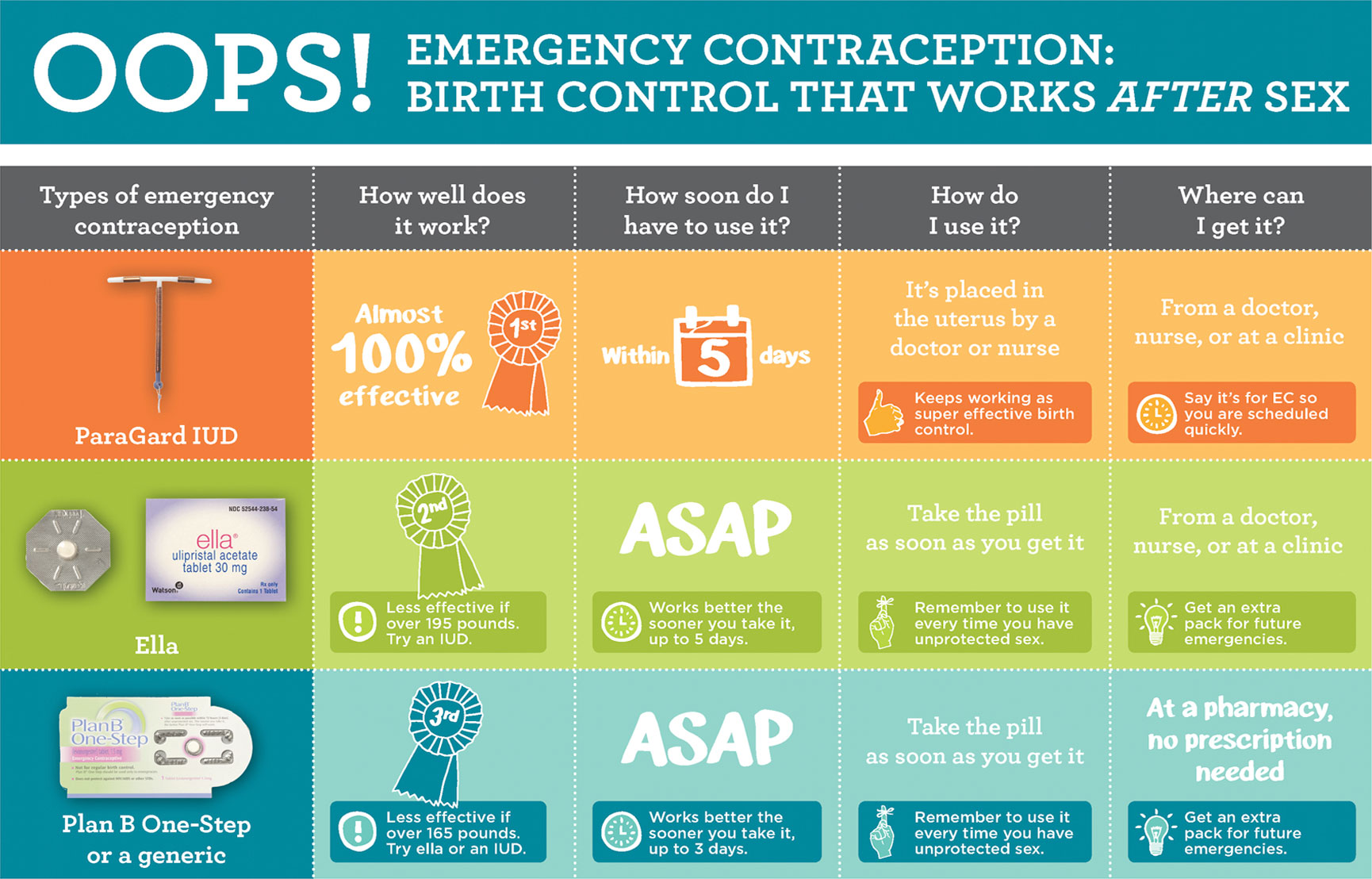

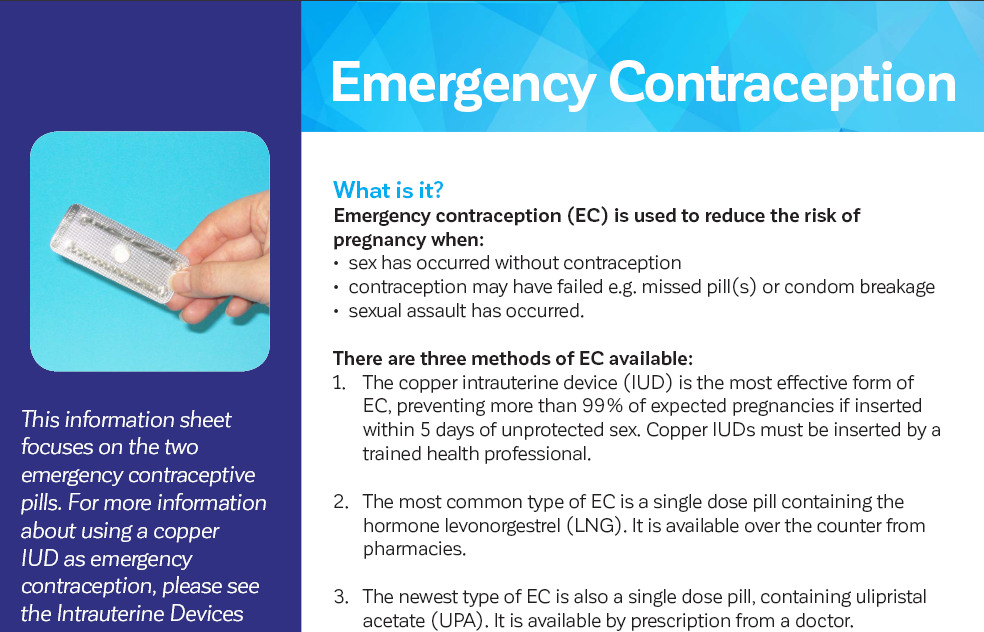

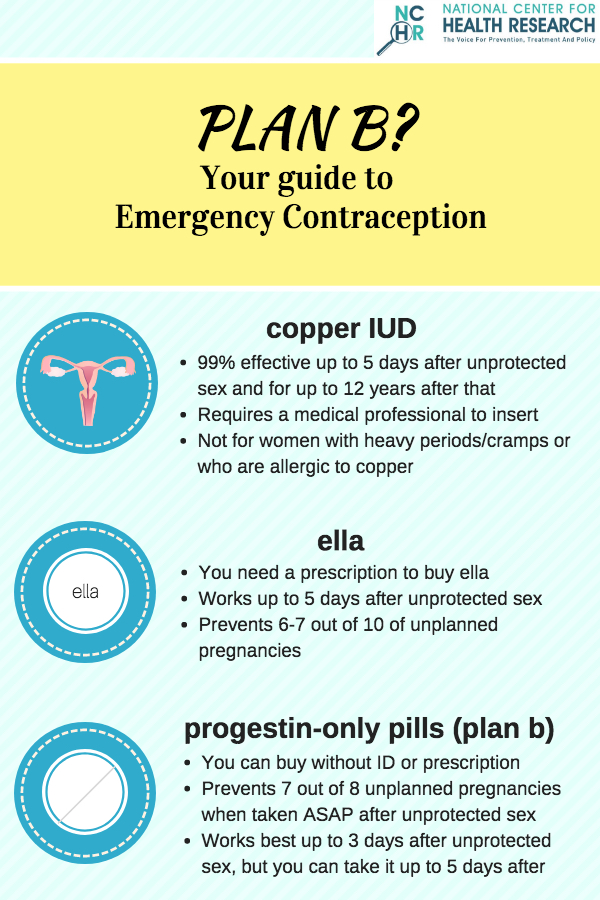

- Women* should be advised of all available emergency contraception (EC) methods at the point of contact and advised that the Copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD) is the most effective form of EC followed by the Ulipristal acetate emergency contraceptive pill (UPA-ECP) and then the Levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive pill (LNG-ECP).

- Health care providers in Australia should provide telephone or video consultations for the provision of oral EC where social distancing needs to be maintained (1), with the option of a delivery or pick-up service of the product to limit face-to-face contact.

- Interdisciplinary collaborations and rapid referral pathways should be established by primary health networks to facilitate emergency Cu-IUD insertion for EC

Recommendations for pharmacy

- Pharmacists should raise awareness that the Cu-IUD is the most effective method of EC and that UPA-ECP has superior effectiveness compared to LNG-ECP.

- Pharmacists should provide information about local Cu-IUD inserting clinicians at the point of contact where women wish to pursue a Cu-IUD as EC.

- Pharmacies should routinely stock both oral EC options (UPA-ECP and LNG-ECP) so that either can be offered to women depending on their medical history (e.g. breastfeeding, overweight/obese), time elapsed since unprotected sexual intercourse and desire to quick start contraception.

- When dispensing EC, pharmacists should advise women of the need for ongoing contraception and provide information as to the range of options available including long acting reversible methods and how to access these locally. Notably, women should be advised that hormonal bridging contraceptive methods should not be initiated until 5 days after UPA-ECP use, otherwise the efficacy of UPA will be reduced (2, 3).

- Where a woman has had a previous prescription for either the progestogen-only pill (POP) or combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) within the previous 6 months, pharmacists are able, under the Continued Dispensing Initiative, to supply one month’s worth as a “bridging method” where effective contraception is not currently being used, or a prescription cannot be obtained (4).

- Third-party access, where an individual may be provided oral EC on behalf of someone else, must be upheld to continue access to EC for those who may have difficulty obtaining it themselves

- Advance provision of EC through pharmacies is encouraged to ensure timely use of EC.

Recommendations for policy

- Cu-IUD provision should be publicly funded at no cost to the woman and available through a variety of services in the community

- A national hotline based on the 1800MyOptions service should be funded to allow women to access information as to the locations of pro-choice pharmacies and IUD insertion providers

- Implementation of national pharmacy guidelines (5) should be supported by government and pharmacy professional groups to ensure consistent, best-practice EC care

- EC methods should be made available free to all women

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, it is anticipated that the demand for emergency contraception (EC) will increase due to an increase in unprotected sex, reproductive coercion, and restricted access to regular contraceptive methods. It is, therefore, critical that emergency contraception services are maintained and continued. The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health (FSRH) UK have identified EC as an essential sexual and reproductive health (SRH) service that must continue during the COVID-19 pandemic (1) as has the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (6).

EC methods available in Australia (in order of most to least effective) are:

- The Copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD). The Cu-IUD is the most effective form of EC. It is effective if inserted up to 120 hours after unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI) and thereafter works as a long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) for ongoing contraception.

- The Ulipristal acetate emergency contraceptive pill (UPA-ECP). UPA-ECP is the most effective oral EC option. It has been demonstrated to be effective when taken up to 120 hours after UPSI with no significant reduction in effectiveness observed with increasing time between UPSI and UPA-EC (up to 120 hours)

- The Levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive pill (LNG-ECP). – recommended to be taken as soon as possible prior to 72 hours (7). While there is still some continued efficacy up to 96 hours after intercourse (8) (use of LNG-ECP after 72 hours from UPSI is off-label) if a woman presents >72 hours post UPSI requesting EC and does not want or cannot access a Cu-IUD then UPA-ECP is preferred over the LNG-ECP due to higher efficacy (4).

Health professionals (including doctors, nurses and pharmacists) need to be aware that ECPs should be available to ALL women* regardless of age or health status (9). Third-party access, where an individual may be provided oral EC on behalf of someone else, must be upheld to continue access to EC for those who may have difficulty obtaining it themselves. In addition, advance provision of EC through pharmacies is encouraged to ensure timely use of EC. Of note, there are no negative impacts on sexual and reproductive health outcomes or regular contraceptive use associated with advance pharmacy provision (6). Consideration should be given to the woman’s ongoing need for contraception and risk of sexually transmitted infections at the point of care with information and appropriate local referrals provided.

The inability to pay for EC should not prevent women’s access to it. This is of particular importance during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen an economic downturn and high job losses. Therefore, the LNG-ECP, UPA-ECP and Cu-IUD should be available free of cost to all women and insertion costs for a Cu-IUD should be publicly funded. We note that oral EC is available free through a variety of providers in the UK (10). Conscientious objection to EC should not prevent women’s access, and objecting providers have a duty of care to provide effective referrals** to women in need of EC.

Oral EC may be preferable during the pandemic, as it requires the least face-to-face contact and is the most easily accessible EC method. Nevertheless, the Cu-IUD remains the most effective EC method with the additional benefit of providing ongoing highly effective, long-acting contraception and should be made an accessible EC option during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Many barriers currently stand in the way: the CU-IUD is not subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and takes time to obtain through community pharmacies (they need to be ordered in and purchased) and there exists an inability to rapidly access Cu-IUD insertion in community settings for the purpose of emergency contraception. Primary health networks are ideally placed to ensure regional level needs are met by establishing local interdisciplinary collaborations and rapid referral pathways to insertion.

Community pharmacies offer an accessible service for timely access to non-Cu-IUD EC, demonstrated by increased rates of access to the EC pill since its deregulation to a Schedule 3 over-the-counter medicine in 2004 (11). During the COVID-19 pandemic, when health care services may be more restricted, pharmacy provision of EC may play an even greater role, particularly for those most likely to experience access barriers, such as women from regional and remote areas. Pharmacy-based EC care also provides an opportunity to improve women’s knowledge of and access to effective contraceptive methods. Although pharmacists perceive the provision of information about contraception and STIs within their role when dispensing EC (9), it is unclear as to what extent pharmacists are currently engaging in this practice (12). Collaborative partnerships between pharmacy and contraceptive providers in the community, may enhance the referral of women seeking EC to obtain highly effective contraceptive methods during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond (13).